First Chapters Q&A with Harry Saddler

Harry Saddler is the author of We Both Know: Ten Stories About Relationships (2005) and Small Moments (2007), a short novel about the aftermath of the Canberra bushfires of 2003, both published by Ginninderra Press. In 2014 he was a join winner of the Melbourne Writers' Festival/Blurb Inc "Blog-to-Book Challenge" for his blog Noticing Animals, resulting in his third book Not Birdwatching: Reflections on Noticing Animals. His non-fiction writing about the ecological, physical and philosophical interactions between humans and animals has been published online at Meanjin and The Wheeler Centre, and in print in The Lifted Brow. He has twice been shortlisted for The Lifted Brow's Prize for Experimental Non-Fiction. Harry will be reading at First Chapters on Friday 7 September from his latest book, The Eastern Curlew.

1. Brunswick Bound has asked you to read a chapter from your published work. Tell us what we can expect from the chapter you have chosen?

1. Brunswick Bound has asked you to read a chapter from your published work. Tell us what we can expect from the chapter you have chosen?

I'll be reading from

the start of my book The Eastern Curlew, which is about a bird of the

same name. The pages I’ll read will give you an introduction to the bird – what

it is, what it does, and (hopefully) why it’s an amazing animal, worth writing

a whole book about. What you’ll be hearing me read is the start of the book, by

which I mean the genesis of the book. So there’s a sense of discovery in

these early pages, I think – for the reader, of course, who might be

encountering the eastern curlew for the first time; but also for me, as a

writer. These pages are me writing my way into a book, and realising that I

could and would and wanted to write a book on this subject.

2. How would you describe the kind of books that you

write?

My writing practice

as it is now is focussed on the environment, particularly animals, often birds

because they were my first love in the animal world. More specifically I look

at how animals exist now within a world dominated by humans: how human activity

is affecting them, and how they in turn leave an impression upon people. If

there’s a fundamental underlying principle to my writing, it’s that we humans

are just another animal, and it’s a lack of understanding of this animalness,

and our place within the animal kingdom and the natural world more broadly,

that has led to the current age of environmental distress and peril.

3. What was the first book that you read (or had read

to you) that left an impression on you?

I’m perhaps unusual

for a writer in that I’ve had two writing careers. I started off as a fiction

writer who never thought he’d write non-fiction; now I’m a non-fiction writer

and I can’t imagine ever returning to fiction. So I’ll talk about my second –

current – career, which began only a few years ago. I started writing

non-fiction when I created a blog, which I called Noticing Animals, in 2011.

For the first year or two of that blog I didn’t really know what I was writing:

it was a strange mishmash of natural history, science, autobiography, and

childhood memories. I didn’t know if this kind of writing was legitimate: did

it even make sense? Then on a trip to the UK

4. Do you believe that books should answer life’s big

questions?

When I wrote fiction

my answer to this was a firm “No”. I think fiction is more effective when it

raises questions, rather than asks them – when it makes its readers think about

questions that they may not have previously considered, or might prefer to avoid.

Now that I write non-fiction – and now that I’m a little older – I’ve softened

a bit: obviously the whole point of much non-fiction is to try to provide

answers to the problems of the world. However I don’t think the particular

non-fiction that I write is suited to that task. Perhaps that’s because I don’t

yet have the confidence – or the hubris – to think that I can answer any of the

big questions. Often in the course of writing The Eastern Curlew I found

myself relieved that my self-appointed role was only to write about the issues

the book covers, and not to try to solve them.

5. What’s your go-to solution for writer’s block?

Just start writing.

Which sounds counter-intuitive, or perhaps arrogant, but it’s important to

remember that a piece of writing can always be reworked later. Obviously it’s

great when the words are just flowing out of you like water from a tap but the

passages that are the hardest to get out are often the best passages of all,

because they’ve been worked and shaped in the course of writing them. If you’re

writing non-fiction it can also be useful to start writing down the facts of

your subject matter: if the facts are sufficiently amazing to capture your

attention, they’ll likely be captivating to at least a few other people, too. Some

of the best passages of non-fiction that I’ve read are nothing more than facts,

presented straight, in plain language. But it’s also important to remember that

– unless you’re working to a tight deadline or you’ve left it to the last

minute, or you’ve signed a binding contract – it’s okay to give up on a piece

of writing, for the day, or the week, or sometimes forever. Not everything

works. Not everything has to be a win.

6. What is your

favourite word or phrase?

My book is about

eastern curlews, of course, but it’s also about all the other shorebirds that

they migrates alongside. Shorebirds have been among us for a very, very long

time, and their names are deeply evocative – of ancient cultures, ancient

thinking, ancient ways of looking at the natural world. While writing the book

I’d return to these names time and time again, like an incantation or a magic

spell: curlew; whimbrel; godwit; snipe; sandpiper; plover; greenshank;

stint; redshank; tattler; turnstone; sanderling; ruff; dowitcher; knot.

7. What do you put down as your occupation when asked?

It depends how I’m

feeling. I have a day-job besides writing, because writing is not a lucrative

way to spend your time and I have rent to pay and pets to feed. Sometimes if I’m

at a party or wherever and I’m just not in the mood and somebody asks me what I

do I might feel like being an uninteresting person for the night, so I’ll tell

them about my day-job. After all, it’s what I spend more time doing than any

other single activity. Sometimes if I’m feeling a bit more chatty I’ll tell the

other person that I’m a writer. That always prompts a lot more follow-up

questions than the day-job.

8. What is the question that you hope never to be asked

in an author Q&A?

One question that

comes up from time to time in regards to this book is: “Why should we care if

the eastern curlew goes extinct?” Sometimes it’s phrased more politely – “What

do we lose if the eastern curlew goes extinct?” I find it a really hard

question to answer. For me the value of any given species is self-evident: it’s

innate. Species have a right to exist in their natural environment precisely

because they exist. What do we lose

if a species goes extinct? We lose the species. Isn’t that enough?

9. What question do you hope you will be asked and why?

“What’s so great

about mud?” That’s a slightly tongue-in-cheek answer, but also a deadly serious

one. We can’t begin to understand animals unless we understand their habitats.

A key theme underpinning my book The Eastern Curlew is my persistent

attempts while writing it to try to see things as they actually are, instead of

relying on received wisdom. That started with the very first passage I wrote in

the book, which was a dressing-down of the nature writing cliché word

“liminal”, specifically as it’s applied to mudflats. Mudflats are very unsexy

habitats. I have a phrase which I trot out a lot which is “mudflat evangelist”:

in the three years it took me to write the book I fell deeply and passionately

in love with mudflats, which are a rich and complex ecosystem. I’m a mudflat

evangelist. Ask me about them.

10. Which book that you have read do you think should

be better known or more widely read?

I’m going to return

to Kathleen Jamie, who I mentioned earlier. She’s got quite a big reputation in

the UK , where nature writing

is big business, but here in Australia island of Rona ,

and one in which she visits a whale museum in Norway

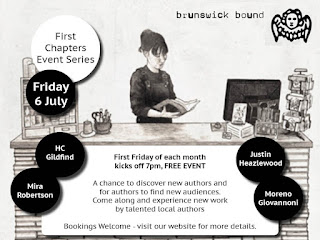

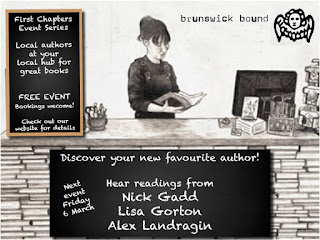

You can find out more about First Chapters on the Brunswick Bound website. Bookings via Eventbrite.

You can find out more about First Chapters on the Brunswick Bound website. Bookings via Eventbrite.

Comments

Post a Comment