First Chapters Q&A with Enza Gandolfo

Enza Gandolfo is a Melbourne-based writer and an honorary professor in Creative Writing at Victoria University. She is also the co-editor of the journal TEXT and a founding member of the Victoria University Feminist Research Network.

Enza's first novel, Swimming (2009), was shortlisted for the Barbara Jefferis Award.

She will be reading from her new novel The Bridge at First Chapters on Friday 5 October.

1.

Brunswick Bound has asked you to read a chapter from your published work.

Tell us what we can expect from the chapter you have chosen?

I

am going to read the Prologue of The Bridge. This introduces the reader to Antonello, one of the two main protagonists,

and to the West Gate bridge. We get a sense of the relationship between

Antonello and the bridge, as well as between Antonello and his wife, Paolina.

The prologue is set in October 1970, a couple of days before the bridge

collapses and Antonello’s life is changed forever.

2.

How would you describe the kind of books that you write?

The Bridge is my second novel. My first

novel, Swimming was published in

2009. They are very different novels but they do have some common elements:

they are both set in the western suburbs of Melbourne, and they both explore

the way that people deal with loss and grief, and with the unexpected events

that can throw life off course. My writing

(short fiction, memoirs and novels) is motivated by a desire to tell the stories

of those people whose lives are often invisible or silenced in the mainstream

culture – in particular women, migrants and the working class. My aim is to

write stories that challenge and broaden our ideas about who we are as

Australians and as global citizens, stories that help us build empathy and

understanding for each other.

In

Swimming, I am exploring what it

means to be a woman without children in a world that equates womanhood with

motherhood. Kate is 60, she is looking back at her life, and the way it has

been shaped by her struggles with infertility. It is also about her

relationship with her best friend and her best friend’s daughter, it is about

creativity, betrayal and ocean swimming. With The Bridge, I wanted to write about the working class, and to tell the story of the West Gate Bridge

collapse, a story that is not only integral to Melbourne’s history, but to the

history of the modern city. While it explores an actual event, The Bridge is a novel and a novel is

always about the characters, in this case, two young people whose lives, and

the lives of their families and friends, are changed due to tragic events; it is

about culpability and guilt, about love and the possibility of redemption.

I

was born into a house with no books. My family were Sicilian migrants and they

did not read English, and Italian books were hard to come by in the 50s in

Australia. However, it was a house overflowing with stories. My grandmother especially

loved to tell me stories, most of these were set in the small village in the

Sicilian hills where she came from. In her stories, there were magical elements

– babies that tamed snakes, spirits that promised treasures in return for favours.

In her telling, these were as real and as ordinary as cooking and washing, as

talking to neighbours or cleaning after the animals. They left an impression

because they transported me to a place that my family called home, but I had

never been, and because in those stories anything was possible.

Once I started to read, I devoured books and so there are

many that left an impression. One is a little-known book called, A Bunch of Ratbags by William Dick. I

read it when I was in Grade 5. It left an impression because it was set in

Footscray. I had never read a book set in my suburb before. I loved seeing my

neighbourhood through the eyes of the narrator. It also inspired me as a

writer, the idea that I could tell the stories of the people I knew.

4.

Do you believe that books should answer life’s big questions?

The

best novels ask the big questions and then explore them through the lives of

individual characters. There are no definitive answers to these questions, but

through reading, we gain insights which we can take back into our own lives. My

writing always begins with questions I don’t know the answers too, I write to

explore those questions.

5.

What’s your go-to solution for writer’s block?

Writing.

Keep writing. Even if what is coming out initially is not great or not even on

topic. One of the things I learnt from being an academic and writing lectures

and papers to a deadline, is that you can work through writer’s block if you

stay with the work, push through it. This works with all kinds of writing

including fiction. Often when I have

writer’s block it’s because I have reached a difficult point in the story – a

dark or emotional scene – and I am reluctant to go there, or reluctant to take

my characters there, but the only way forward is to push through. Of course,

there are times when its best to have a break, in those times I find going for a

swim or a walk and letting my mind drift into a kind of dream space helps.

6. What is your favourite word or phrase?

One of my mother-in-law’s sayings is a favourite of mine – fare un buco nell’acqua which translates

to ‘making a hole in water’. Perfect saying when you have to cut the paragraph

you spent all day writing.

7.

What do you put down as your occupation when asked?

Until

recently ‘academic and writer’ and now ‘writer’.

8.

What is the question that you hope never to be asked in an author Q&A?

Nothing

comes to mind. I love being asked new questions, challenging questions I

haven’t been asked before.

9.

What question do you hope you will be asked and why?

I

love it when interviewers and readers ask questions that are surprising and

that I haven’t thought of myself. Often

readers see things in a novel that the writer doesn’t see, each person brings

their own life and their own experiences to a novel and it makes the work

richer. I look forward to the surprising

questions.

10.

Which book that you have read do you think should be better known or more

widely read?

Rosa

Cappiello’s Oh Lucky Country was

published in 1984. She was an Italian migrant living in Australia. She wrote

the novel in Italian and then it was translated into English. This is a

passionate, angry and often confronting novel about alienation. Unlike other

novels classified in the ‘migrant writing’ genre, there is no grateful migrant or

‘migrant as victim’ here. The protagonist, Rosa is a sharp and critical

observer of Australia and Australians. She

explores a number of issues: gender and class as well as ethnicity. The

language is playful and the text is experimental. It is often left off the list

of Australian classics, but I think it’s an important Australian novel, that

still has much to say about identity and nationhood and the way we see

ourselves as Australians.

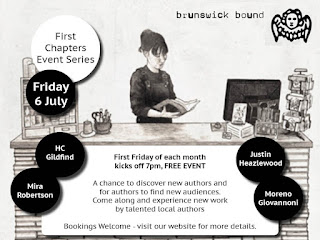

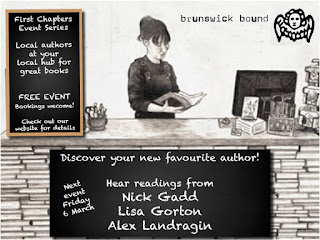

You can find out more about First Chapters on the Brunswick Bound website. Bookings via Eventbrite.

Comments

Post a Comment